Written by Tanja Berretta, Director of Master HOPE – Humanitarian Operations in Emergencies SCS Board Member and Humanitarian Expert

I have been scouring sources and news stories for days and trying to write something sensible about what is happening in Afghanistan. I have been asked to do so by many people these days, and my studies, my work, my institutional role at the Social Change School and our students – in short my whole adult life – demand it.

But I want to remain, especially in this occasion, as honest and direct as possible, even at the cost of appearing unprofessional. And so I will say that it is not possible for me to analyse or offer anything rationally accomplished and sensible: because my thoughts are muddled and scattered in an incoherent myriad of sources and analyses over the last 20 years, and above all because my heart and chest are ripped open.

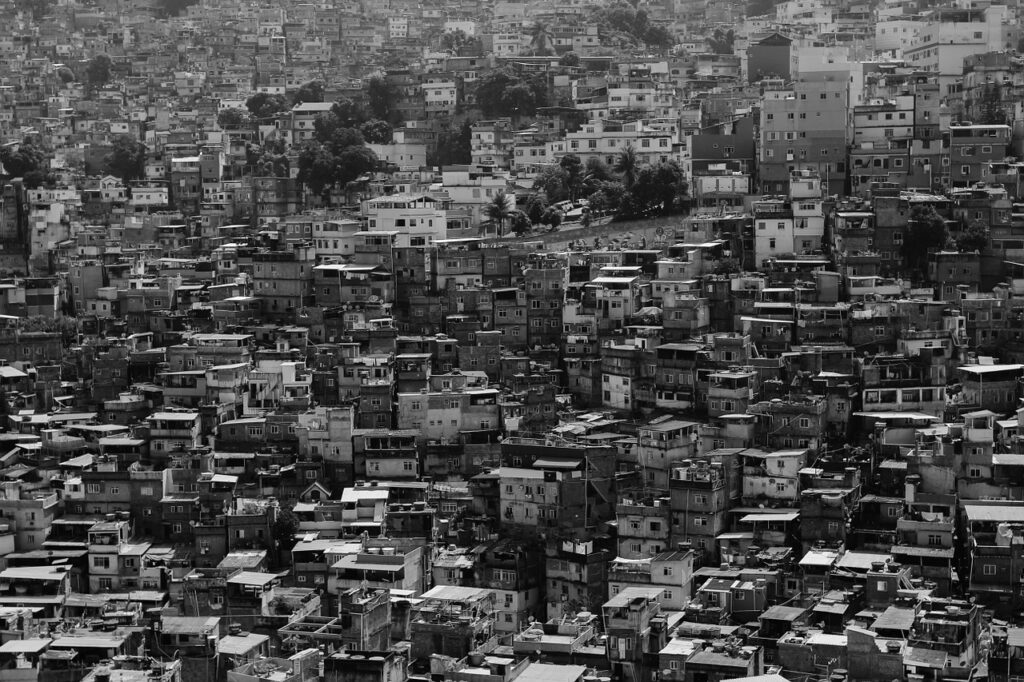

Because for me Afghanistan has never been and never will be simply a place where I have lived and worked for almost three years and returned to again and again, it is not a “complex crisis” and it is not an example of potential Triple Nexus strategies, or community resilience, women empowerment or governance.

For me, Afghanistan has always been – and is even more so these days – an obsession, a torment, a love story that has never been resolved, an unsolved enigma, the sum of all the hopes, contradictions and failures of my profession, my sector – and perhaps existential. So, I cannot be objective, neutral, nor, obviously, professional. Because I am madly in love with this brutally Beautiful country, its heart-breaking complexity, its troubled history and, of course, its people, the stories of the people I have crossed paths with, worked with, become attached and forever connected to.

I owe a huge debt to Afghanistan for all that it has allowed me to live and that it has taught me: professionally, humanly, spiritually.

Nothing has been the same for me since Afghanistan. Afghanistan taught me brutally about fear, which I saw in too many eyes and heard in too many voices. And it enlightened me with the courage of Women and Men for whom being born where and how they were born had taken everything, and who instead of giving up snatched a chance to live tooth and nail. But above all, it has taught me humility in attempting the impossible exercise of understanding a complexity that in Afghanistan seems to shake and confuse everything: geopolitics, history, political doctrines, religion, theories of development.

Frankly, I’m reading a lot of rubbish, and I don’t recognise much in the way of reliable sources at this juncture (it must be that I have a penchant for primary sources, and that I don’t digest stormy journalism – I’m evidently referring to CNN’s sketches on the streets of Kabul today). But there are also geopolitical and historical analyses that seem to me to be valid, and that get to the heart of the matter (mainly following the strands of the Taliban leaders of the world drug trade, Afghanistan’s key role in the international energy transition as El Dorado of lithium, bauxite, copper, iron and rare earths, and the evergreen protagonist Pakistan in the Afghan question).

In parallel, all the hypocrisy and ignorance of the debacle around the new generation of Taliban and the trampled human and civil rights. As a sociologist of development and as a humanitarian worker there is perhaps only one thing I can say very strongly about this: that Afghanistan was the Middle Ages in 2001, and that 20 years of war have not allowed Afghans to live these 20 years as a real opportunity for economic, social and, I would add, cultural development. Because when there is war there is only war (and a thousand analyses explain why Afghanistan has been plagued by war since time immemorial). There are no theories or development strategies that hold when there is war, let’s stop saying that Afghanistan had its chance and lost it. To put it in a brutally concrete way that my friends and colleagues in the humanitarian field will recognise well: during a conflict, during a disaster, we try to limit the damage and work for the resilience of communities, families and individuals, at the same time trying to get out of the logic of the emergency cycle.

But in Afghanistan the war never ended: with the end of the Taliban regime in 2001, millions of refugees who had fled 20-25 years earlier began to return to their country, and the flow of re-entry has continued for the last 20 years. Finding occupied property and rubble, having lost all their rights, still encountering war and military occupation, and eventually remaining displaced at home. A process of that magnitude already has immense economic, social and cultural repercussions in the development process of a country. Today, the children, the grandchildren of those people, and perhaps they themselves are running away again from their land, from their roots, from their everyday life.

The Afghans have never had any real opportunity for development: it’s not as if until a week ago the country was the picture of women’s emancipation, child protection, economic development, etc. etc., so let’s not wake up to that now. And, I conclude, even if Afghans had been able to enjoy these last 20 years in peace in their land and do what they wanted/could have done with it, socio-cultural development processes follow times and dynamics peculiar to the context, but we would hardly have come out of the Middle Ages in 20 years.

I am petrified by the events of these days, because I know that so many Afghan friends, sisters and brothers are in danger for the mere fact of having tried to get out of survival and live in these years, despite everything and everyone. And I am petrified of anger because in the immediate future there is no alternative to humanitarian corridors to be urgently established for those who flee (which cannot be defined a priori and limited to women and children, since non-Pashtun ethnic groups, human rights activists, LGBT+ people without any possible protection, women journalists, teachers, students, health and social workers and those who have worked in humanitarian and development programmes with international organisations and many others run enormous risks).

Anger because everything is still silent in this regard, and it is exceptionally serious that there are still no concrete signs and that days pass marked by institutional telephone calls and timid declarations of realpolitik, when every minute that passes is a minute of terror that could be fatal for so many people and families who at this very moment are facing another night of waiting and horror. IT IS DISGUSTING.

Italy was the first country to successfully experiment with “humanitarian corridors”, and it has the responsibility to intercede with Europe so that a European humanitarian corridor can finally be opened. In order to complete the minimum immediate actions for which Europe must finally take responsibility, the member states should also suspend open expulsion practices, and then help the Afghans who are already living in precarious conditions in Europe.

This silence is, I repeat, utterly deplorable from every point of view: institutional, political, and once again, human.

It is likely, indeed evident, that a good part of the population has chosen over time to be with the Taliban: the capillary presence on the territory has been prepared over the years and no guerrilla warfare can be successful without popular support. Choose to be with the Taliban or with the occupying foreign military? Or with none? Or with the local warlords? It is impossible to take a clear picture of the dynamics of a civil war as events unfold. The gash of a people, once again.

In the heartbreak of these days, I went to reread my diaries and notes from my years in Afghanistan, and I think that in the end, if there is anything I can share with those who ask me to say something, well, it was already all in the lines of that young me who arrived in Afghanistan the day after the start of Enduring Freedom, finding a country that was hungry and hungry for peace, and who fell madly in love with this extraordinary and complicated place where nothing is what it seems, and which still deserves, even today, simply that chance. But above all, it deserves so much respect, so much humility and so much compassion.

“Evening, or rather late night here, almost 10 o’clock and all is silent, apart from the crazy helicopters that disturb the peace around us. The journey from Mazar yesterday was long and overwhelming, as always. I don’t think there is anywhere more damn beautiful than northern Afghanistan. The orchards of Pul-e-Khumri, the canyons of Badakhshan, the valleys of the entire Panshir, the magnificence of the Great Mosque of Herat, the wind and the blinding blue sky of Bamyan, the sand, dust, rock that eat away at your skin and hair, the frost, the cold that gets into your bones and stomach. And the Turkish snack market on Fridays in Kunduz. All this beauty hurts.

On my way to the office this morning, I got lost in the city. Already at 6 o’clock swarming with yellow taxis, I got lost in the crowd in a bazaar just outside the centre of Kabul. In flashes I could see suicide bombers everywhere. A while ago, a Chechen girl was arrested with explosives ready to blow herself up in front of the gate of an American NGO where a dear friend of mine works: this morning, being stuck in traffic offered me a new light through which to see suicide bombers. Understanding the desperation with which the decision to blow oneself up is interpreted has no place in my daily reality at the moment. A matter of survival, crude to say, and even more so to hear.

At the end of March I will be leaving Afghanistan, perhaps sooner, after almost three years of daily life here. I think of the women, the children I have met, the thousands of looks, voices, smiles… the thousands of snapshots stored in my mind.

After three years, I am back where I started. About the analyses of us other “social scientists”, and ultimately of myself. The images of the new post-Taliban Kabul in the various magazines from around the world with driving schools for Afghan women to enrol in do not represent the reality of this country at all. Divided into a thousand portions on a geographical, historical and ethnic basis. Tajiks, Pashtuns, Uzbeks, Turkmen, nomadic Gujurs. Nomads and sedentary, breeders, traders, farmers. Matriarchal and patriarchal communities. Divided along the lines of the zones of influence of local squires who enslave unsuspecting opium farmers, behead girls promised in marriage at the age of ten for crying or showing a reaction, plunder, loot and terrorise. The power system is somehow less complicated, no ‘sweetener’ to mitigate: power here is evident, transparent, you live it, you see it, you touch it every day in everything, at every encounter, in every situation. No consumer fog, no space for contestation, no Desire, no daily alternatives: either you stay or you die. Take it or leave it. And it almost doesn’t make you angry, because it is evident, not hypocritical, disarming, lucid, you see the effects: blatant, clear, not twisted. The Horror of War. What analysis can you make of the Horror? I ask myself this constantly, obsessively. The almost banal Horror of the daily actions of human beings on other human beings. Here there is no room for analysis, explanation, strategies and actions other than the daily survival of brutality, the wrenching out of the torment of one out of a thousand (which you ‘choose’, knowing consciously that you are leaving another thousand to the slaughter), the attempted diplomatic mediation with ridiculous and very powerful characters that you cannot even look in the eyes, but with whom you have to deal, to try to wrench out of the slaughter two, instead of one, of those thousand.

In these three years here, the awareness acquired daily of how much presumption analyses and strategies bring with them. Western-centric, as always. How much hypocrisy and partiality my readings, my years of honest study, have fed on. A thousand discourses. Human rights, the needs system, capital, possible worlds. My presumption, my analysis as a good sociologist of development, my long years of ‘black and white’ incinerated in an instant, by the blink of the eyes of a child who can barely walk, whose name you don’t even know, whom you meet in the corridor of a – so-called – prison, the one in which perhaps he was born and in which he will burn the best years of his life. And you raise your eyes, looking for who knows what, for a Why perhaps, for an immediate and pacifying explanation read in some book or manual, but Nothing, Emptiness, in front of you there is only his mother, who looks at you fixedly in the eyes, with a mixture of serenity and severity, her skin burnt by the sun and the frost, by the desert, by the war, by an ungenerous life, a rag on her head, a ragged apron under which she hides her hands. And you wonder why you are there, and how you allow yourself, with what unforgivable and immense presumption, to be there.

Millions of questions. No answers.

I don’t know how many of all those who are here (me, first of all) have honestly, consciously listened to the stories, the desires, the pains, the wishes of the Afghans. For real. And have inspired what we are here for in them. Many I believe have. But many, too many do not, not yet.

This is my present. And the present of the dozens of people I meet every day and who I came here to “help” through my thousands of studies and analyses. I also spend my nights looking at myself, in silence, waiting for who knows how the next day will come. Often I am just scared. And compassion becomes in me the only response to a present lived in the midst of these snapshots of brutality. The sense of compassion and respect for the ordinary, tiny daily efforts of extraordinarily strong and proud Human Beings, who did not deserve this land plundered, humiliated and tortured by so many, by too many”.