Bernard Ross | 4th July 2013

Bernard Ross with help from Angela Cluff and Paula Guillet of = mc

A powerful movement to encourage major donor giving has been labeled philanthrocapitalism. The name comes from an influential book of the same title published in 2008 and an associated website. Two journalists working for the Economist magazine, Matthew Bishop and Michael Green, wrote the book.

The philanthrocapitalism argument is simple and in many ways compelling, especially in our current economic situation:

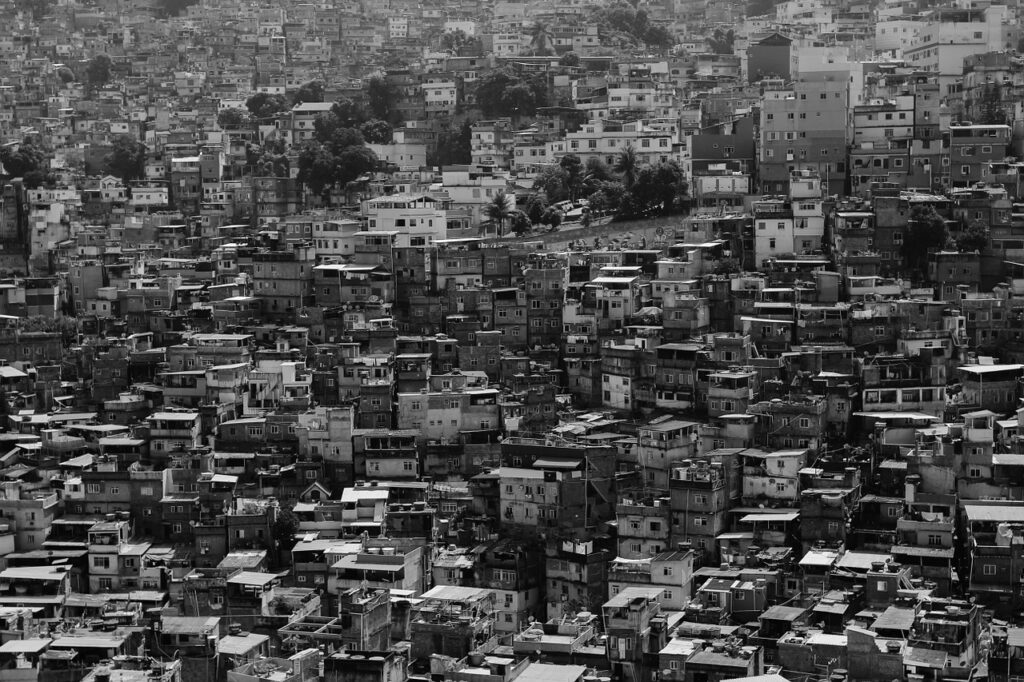

• There’s a need for a “leadership force” to tackle the big social issues of our time:

poverty, climate change, health inequality, and so on.

• In the past century we have expected our governments, by and large, to tackle these challenges either directly or through social programs and policies.

• Sadly governments seem to have had mixed success at tackling

many of these issues even those that see it as a fundamental part of their work.

• The continuing financial challenges in many parts of the world

means that social budgets are diminishing and governments are scaling back activity.

• Entrepreneurs have a track record of applying efficient thinking

to solving challenges and these skills could be applied elsewhere.

• An innovative partnership approach to solving problems is possible, where governments business and nonprofits can collaborate in new ways.

So far so good … and now the interesting bit:

A number of wealthy entrepreneurs and business leaders are taking the lead in creating those new solutions and partnerships to solve social chal-lenges. They are putting more than just ideas into it; they are backing it with money and asking NGOs and governments to join with them. Bill Gates is the obvious example, but there are others from Arpad Busson in the United Kingdom to the Tata family in India and Jet Li in China.

Bishop and Greene note that implicit in the philanthrocapitalism thesis are two key ideas that to some extent confound previous think-ing on the rich and businesspeople in particular:

• One is a rejection of the idea that business is exclusively about profits with little concern for the consequences to society or environment.

• Second is the belief that “the winners” from our economic system should give back and that business can “do well by doing good”.

Philanthrocapitalism has some powerful champions endorsing the broad concept, among them Bill Gates, Bill Clinton, George Soros, and Richard Branson. The Giving Pledge, for example, contains many of the philanthrocapitalist ideas.

As governments cut back their spending on social causes, it may prove to be a significant force for change in society.

But philanthrocapitalism is not universally admired. There are criticisms that the philanthrocapitalists are naive and underestimate the complexity of the social problems they seek to resolve. Or that they have no mandate. Or that they pick and choose issues that appeal to them and not those that are most urgent.

There are even those who worry that Gates, specifically, may achieve “market domination” in global health issues the way his company Microsoft was once the lord and master over the software and computer industry. The concern here would be that his funds draw skills and expertise to the issues that he believes are important rather than those that are most pressing. Critics also worry about Gates’ legitimacy in terms of a power base.

He can and does negotiate directly with governments. In this setting who is he accountable to? And there have been criticisms that some of his initiatives—for example, that the Global Fund has been no more efficient than governmental or NGO efforts.

Despite these concerns Gates and the other philanthrocapitalists continue to attract a great deal of interest.

Bill Gates made his money by building up Microsoft over 20 years. In 2008 he stepped down from operational control. He and his wife, an active partner, now give almost all of their time to looking after the work of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The foundation has spent $26.2 billion since its inception in 1994. It has a number of pro-grams, some domestic to the United States. But it is best known for its focus on eradicating infectious diseases in the developing world.

By setting up and promoting the foundation, he has inspired other rich people to join him in the Giving Pledge.

Gates knows than even his vast wealth cannot solve the challenges that he is keen to tackle, so he has set up a number of projects and agencies. As well as the work of the foundation, Gates has supported two major initiatives: the Global Fund and GAVI.

About the Giving Pledge

The Giving Pledge is a movement of HNWIs and UHNWIs who are publicly committed to giving away the bulk of their wealth to good causes. (The website of the Giving Pledge states that it’s “an effort to invite the wealthiest individuals and families in the United States to commit to giving the majority of their wealth to philanthropy.”) Although formally based in the United States, the campaign has sought in recent years to spread its philosophy internationally with mixed results.

One attractive aspect of the Pledge is its flexibility. The donation can happen during the lifetime or after the death of the philanthropist. Another feature that appeals to potential Pledge signers is that the Pledge is a moral commitment to give, not a legal contract (although as of yet no one has reneged).

Almost 100 U.S. billionaires have joined this campaign and pledged to give 50 percent or more of their wealth to charity. At least $125 billion total had been promised from the first 40 donors based on their aggregate wealth as of August 2010. Despite the recession the number of pledgers and the amounts pledged is growing.

Philanthropist Warren Buffett, one of the early signers, was an admirer of the Gates Foundation and its goals and so saw it as a channel for his philanthropic intentions. Buffett committed much of his wealth to the Gates Foundation.

In 2006 Buffett and Gates began discussing how to encourage other wealthy entrepreneurs to commit their resources to philanthropy. They decided to host a series of dinners bringing together some famous names, including Michael Bloomberg, Oprah Winfrey, and Ted Turner, and asked others to do so as well.

At one of these dinners Marguerite Lenfest, one of the invitees, proposed, “The rich should sit down, decide how much money they and their progeny need, and figure out what to do with the rest of it.” This statement was the inspiration for the Pledge.

In June 2010 the campaign for the Giving Pledge was formally announced. Gates and Buffett announced that they would be proactively contacting potential signatories.

The two philanthropists then declared that they would travel to meet wealthy individuals in Europe, India, and China to talk about philanthropy and the idea of the Pledge. The idea was not universally well received. German and French millionaires met with Gates, but only a small number signed up to the Pledge. French billionaires Arnaud Lagardère and Liliane Bettencourt were approached directly by Buffett, but they refused to commit to the Pledge.

Some of the most strident criticism of the Pledge approach came from Germany. In an interview with Der Spiegel magazine, Peter Krämer, the Hamburg shipping millionaire who has donated millions to UNICEF to support schools in Africa, criticized the tax advantages U.S. philanthropists had that elsewhere did not exist. His argument? “The rich [in the United States] make a choice: Would I rather donate or pay taxes? The donors are taking the place of the state. That’s unacceptable.”

In China and India there was polite interest, but no real commitment as there had been in the United States. Buffett and Gates tried to be sensitive to this. They wrote an open letter to the official Xinhua news agency:

“We know that the Giving Pledge is just one approach to philanthropy, and we do not know if it’s the right path for-ward for China. Some people have wondered if we’re coming to China to pressure people to give. Not at all.”

They continued: “Our trip is fundamentally about learning, listening, and responding to those who express an interest in our own experiences. China’s circumstances are unique, and so its approach to philanthropy will be, as well.”

There has been some success with this more diplomatic approach. Xinhua subsequently reported that Chinese millionaire Chen Guangbiao will leave his entire fortune—some $440 million-to charity after his death. He also claims that he has convinced more than 100 other industrialists to give away their personal wealth. Guangbiao has said, “Although the pledge makers do not want to be exposed to the media, I give my sincere respect to their charity spirit.”

There are still questions about how much influence the Pledge will ultimately have outside the United States.10

A recent discussion triggered by the Giving Pledge is that of impact investment. The buzzword as reported in the Economist in May 201211 was the hottest topic at the second Giving Pledge meeting, organized to share experiences and improve giving. The meeting was held behind closed doors in order to create a safe environment for investors to share giving experiences, including failures.

The term impact investment remains a loose one, and a new meeting will be dedicated to investigate it more fully. But the fundamental idea of following through and paying attention to the effects of investments can both be read as a criticism of the Giving Pledge and an extension of it-a criticism because it points out the limitations of the Pledge’s focus on the amounts and share of wealth donated rather than on what the money actually does.

It raises the question of the measurable effect of the donation, what is changed by the transfer of wealth.

It can also be read more positively as a way of expanding the Giving Pledge by involving the wealthy not just in philanthropic giving, which is bound to involve just a share of their wealth, but in their overall wealth creation and management.

What we have seen so far may only have been a soft start of what the world’s rich can do to save the world.