Alain Vidal | 10th February 2015

The sheer scale and urgency of our world’s food security mega-challenges require action from many partners.

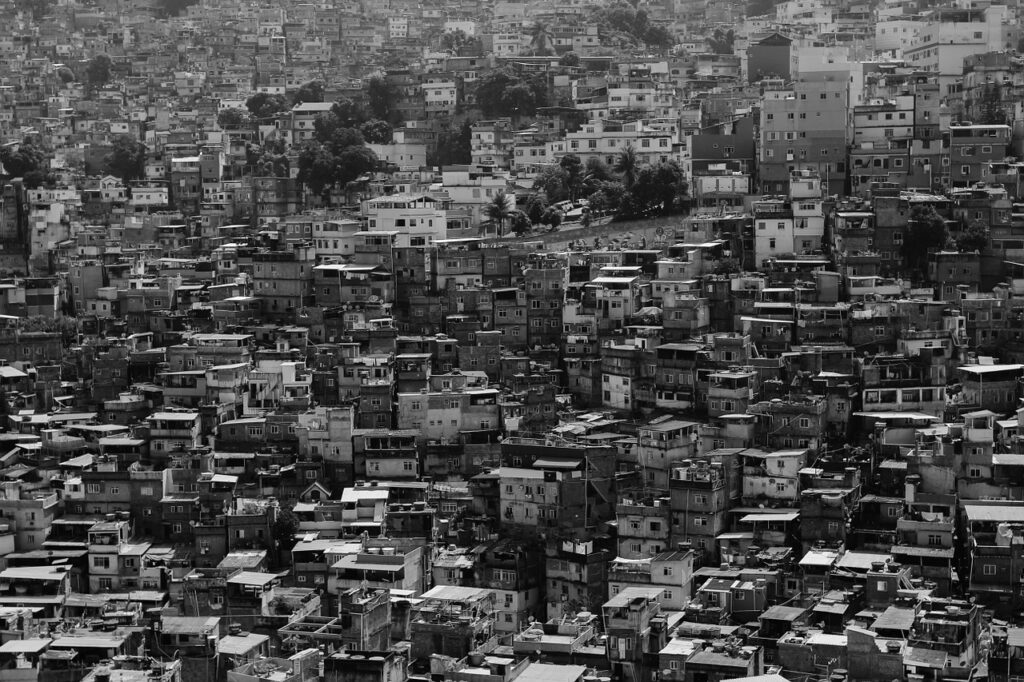

Further, reliable food systems, including value chains, markets, infrastructure and consumption, are critical for human health, nutrition, wellbeing and equity. Producing sufficient and quality food for 9 billion people by 2050 is in itself a daunting challenge for agricultural research for development. We need access, stability and safety in food systems to achieve food security and nutrition for all.

Despite significant progress in addressing the needs of the world’s poorest in the first part of the 21st century, 800 million people still don’t have enough to eat, and 1.2 billion live in extreme poverty. Additionally, climate change, cumulative environmental stress, conflict, dietary-induced obesity, zoonotic diseases and other stressors have slowed or reversed advances in both developed and developing countries. At the same time lack of investment, incentive structures, market failures and consumption patterns result in 40% of food being lost or wasted – an enormous misuse of our limited resources pointing to undervaluation of food and subsequent under-investments in food systems.

The number of groups involved in agricultural research for development has increased and diversified dramatically amid these new contexts and challenges. These groups now include national research systems in some larger developing countries, universities and research institutions in both the developing and developed world, regional and local NGOs, and the private sector. We need strategic partnerships between all these actors in order to tackle these mega-challenges mentioned above.

So how do we make these AR4D leadership coalitions work in an ethical and inclusive way? How can we ensure that actors stay focused on their common objectives? After all, we all share the goals of reducing poverty, improving food and nutrition security and health, as well as improving natural resources management and ecosystem services.

The Global Alliance on Climate-Smart Agriculture (GACSA) launched during the UN Climate Summit in New York last September is a good model as it brings together governments, major NGOs, research institutions and private companies. In this regard, it is similar to the multi-stakeholder model promoted by the Global Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation that came out of Busan. It also presents common challenges. Let us look at some of them.

First, because of the diversity of GACSA partners and how they are represented, the forum runs the risk of replicating a UN model, particularly when dealing with contentious issues. Discussions under this model lean towards a consensus body, where all actors must agree on all action taken, which often stymies progress. For GACSA in particular, the types of issues that could tempt the coalition into behaving like a consensus body could be the development of strict criteria and certification modalities to define what counts as “climate-smart agriculture”. Although we should not overlook consensus-building, I believe it is wiser to ensure that coalitions stick to operating a “leadership model” instead, which happily, GACSA wishes to do. This model seeks to promote direct action on the ground by sharing inspiring examples from those on the ground, knowledge on practices and approaches, and individual commitments from members.

The second obstacle I see is criticism voiced by a large group of civil society organisations who fear that GACSA would actually promote “corporate-smart greenwash” including the promotion of Genetically Modified Organisms, and not care for the poor and vulnerable.

These fears are to a large extent unfounded, since the major, publicly funded international founders of GACSA, such as the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation, the Global Forum on Agricultural Research and CGIAR are quite careful about potential ‘hijacking’ of such initiatives, and each have a mandate to serve the best interests of the world’s poorest people. This opinion is not shared by all. Some civil society organisations have actually joined GACSA.

As researchers, we should be “listening to those doubting, because there is nothing to hide” as Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General for Food Security and Nutrition David Nabarro stated in The Hague. But this may not suffice to get all on board.

Therefore we should be ready to handle “nonbelievers” who want to stay “on the outside” and perhaps even value their role, as it guarantees the ethical and inclusive nature of the coalitions we engage in. One way of doing so could be to create a dedicated, independent advisory committee or panel that includes, or at least carefully listens to, these “nonbelievers”.

I believe these are two key ingredients to making agricultural development coalitions for development work and two major factors to be considered by other development fora like the Global Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation. We need dynamic interaction between members, and active engagement with critics. We all want a sustainable future for our food system and I believe these steps can take us there.