Let us introduce you to another member of our staff, who’s another strategic element of Social Change School.

Bruno supports and assists students in discovering their vocation, enhancing their skills, and creating networking opportunities between master’s students, alumni, and Third Sector organizations looking for personnel.

Can you share with us your personal and professional background and tell us why you chose to work for Social Change School?My background starts far back. Let’s say it can be divided into three phases.

The first phase is that after attending a vocational school for mechanics in the mid-1980s, I worked in this field for several companies in Italy. In the mid-1990s, I began developing the idea of going abroad as a volunteer. My persistence in seeking an opportunity after a couple of years of attempts gave me the chance to use my mechanical skills to volunteer with the Capuchin missionaries in the Central African Republic. I left in January 1998 for a one-year volunteer experience managing 5 member of a team which was in charge of the garage and the foster home of the diocese of Bouar , but I ended up staying for two years.

With the missionaries, I learned how to interact with different cultures and not to get discouraged but to persevere in order to achieve results. This “savoir-être” helped me a lot for the future in the field of cooperation. I was quite young, I was 25 years old, and this experience allowed me to get to know the African continent and realize that I had adaptability and that I was suited for the life of a humanitarian worker.

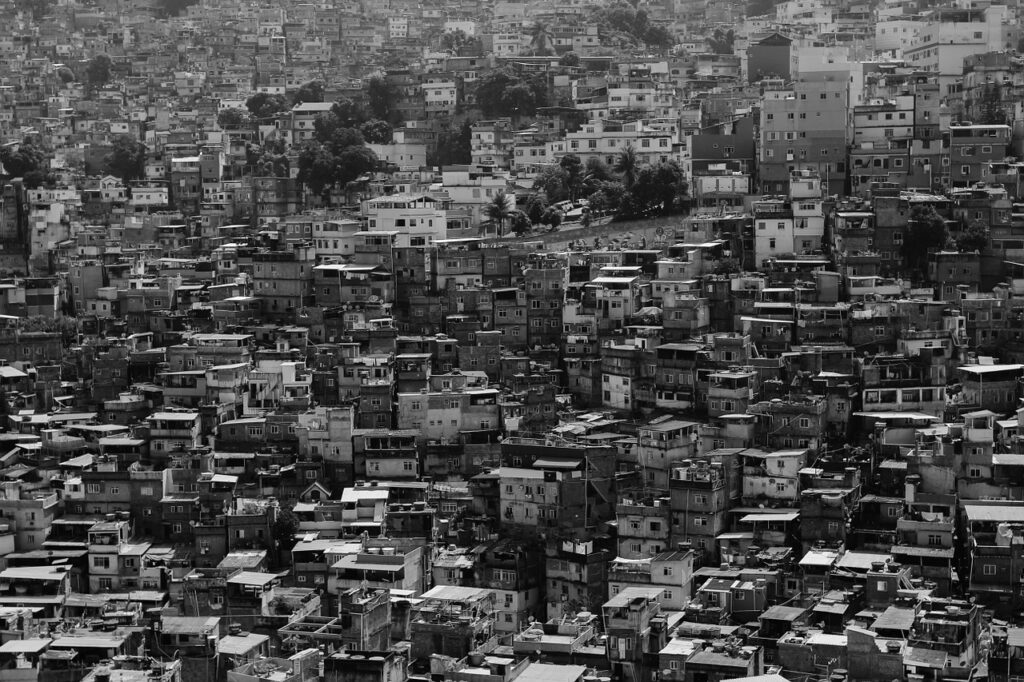

When I returned to Italy, I took advantage of an opportunity for a training course by Intersos for humanitarian demining in 2001. Here, given my background, I was directed towards logistics, and I had the opportunity to work with Intersos in Angola as a logistician for a humanitarian demining project. After Angola, I worked in Niger with ICEI, and then I started collaborating in February 2003 with COOPI, with whom I remained for 10 years, with missions in the DRC, Chad, CAR, Mali, Haiti, Nigeria, and also at the headquarters in Milan. Most of the programs I worked on were in emergency and medium-to-long-term crisis contexts.

Between the end of 2012 and part of 2013, I worked with a French NGO, Handicap International, in Burundi. Since, at that time, the French and Belgian sections of the organization were merging, I handled the fusion of the logistics teams, standardizing all the logistical procedures in place and training the teams. After that, Handicap International proposed that I work on merging the logistics teams in Asia, with the staff from Laos, Cambodia, and Thailand (2014-2015). In these last cases, the projects were development-oriented and not emergencies, so I could see the differences in working in the two contexts, particularly in terms of pace and organization.

Since 2017, due to family reasons, I started working “remotely,” and having acquired skills in staff training, I began collaborating with various platforms and organizations for education and training of humanitarian workers, particularly with online or “on-demand” platforms but, on some occasions, also face-to-face or in-classroom settings. This led me to collaborate, among others, with Social Change School for webinar-based trainings on procurement and logistics procedures.

What is your vision of the Career Development service and how do you think it can positively influence the career path of students?

Although I do not have a specific HR background, being an international aid worker myself, having trained many students over the last 7 years, and having collaborated as a consultant with numerous civil society organizations, my understanding of the needs from both the NGO and student perspectives should lead Career Development Service to expand its scope and network. Gradually, the aim would be to give the service an even more “international” approach, by also conducting job searches by geographic area (with Middle East, West Africa, Asia, Latin America Hubs) and with NGOs and international agencies. Many international organizations, for example some from Northern Europe, have very developed internal welfare policies, which allow them to build loyalty among aid workers and have a less pronounced turnover compared to other organizations where there are fewer “benefits” for the aid worker.

I would like to structure the CDS so that it becomes increasingly a point of reference for organizations, receiving their vacancies, exchanging opinions and perspectives, and at the same time a “Community” for students and alumni of the Social Change School to feel part of something special.

What advice would you give to students who wish to pursue a career in the Third Sector but do not know where to start?

If you don’t have practical experience, you need to make the most of your other strengths, which are theoretical skills that can be acquired through study (and in this, Social Change School’s Masters are a very useful tool), as well as attitude and behavior. HR departments in third sector organizations operate within the same parameters as “for-profit” companies in the sense that they are looking for staff who have skills and capabilities, but at the same time, who can offer temporal availability to be worth investing in. Obviously, in 2024, you can’t ask young people to volunteer/work as aid workers like in the 1980s when people would leave for Africa with a one-way ticket and return after 2 or 3 years. However, making it clear that with the right conditions (taking into account complex contexts), one can be available to stay with the organization for the medium to long term is certainly a good starting point.

Work in the third sector requires a range of skills, from project management to logistics, administration, nutrition, agricultural development, protection, and much more, but these skills are difficult to implement in a work program if you leave after 6 months. From personal experience, I can say that staying in a position with an NGO for a long period helps you understand your progress and notice how a recurring problem can be solved more efficiently the second or third time when you have gained more experience.